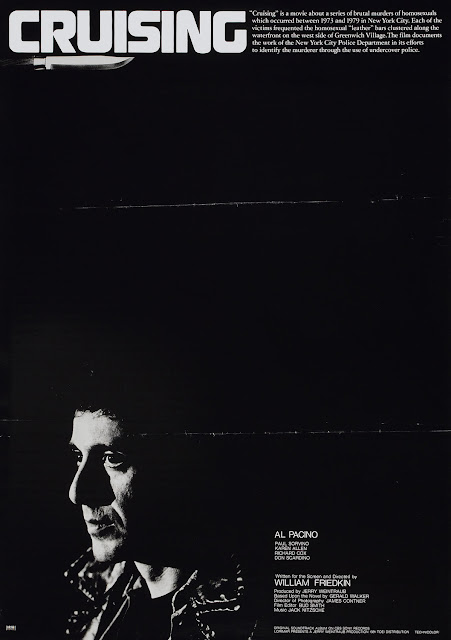

A couple of months ago now, my local arthouse played Cruising as a tribute to the late William Friedkin. I had never seen it before, and I was in the middle of a Friedkin reappraisal (I recommend reading his 2014 autobiography, The Friedkin Connection).

Cruising is a fascinating movie, particularly in the construction of its protagonist.

Cruising was originally supposed to star Richard Gere in the lead. On the basis of American Gigolo, in which he plays a possibly queer sex worker, one can see the potential.

Gere has an androgynous quality, a physicality and sexuality that is not based on machismo, or at least the same expression of masculinity that eventual star Al Pacino embodies.

But there is something more interesting in having Pacino as the lead. There is a sadness and pathos to his portrayal, even before Steve goes undercover. There is a sense of self-denial, as if the character is hiding a piece of himself.

After watching Friedkin’s other tales of self-destructive lawmen, it is easy to see Pacino’s Steve as a spiritual sibling to the leads of The French Connection and To Live and Die In LA.

Friedkin had a fascination with masculinity, its rage, insecurity and self-destructiveness. To that end, Pacino’s frayed performance feels like another facet of Friedkin’s project.

While the film is interested in showing a specific subculture, the film’s focus on Pacino is not as a straightforward audience surrogate.

The film almost seems more interested in Pacino as an object, to be looked at. His gait is lumbering, his voice a low growl. He seems ill at ease, out of his depth.

Whether influenced by the offscreen context (the film’s location shoot was consistently protested for the film’s exploitation of the LGBT community), Pacino’s awkwardness feeds into the character’s own journey.

He spends the movie in an extended makeover. He is forced to confront how he presents, and he begins to question himself.

Despite some explicit visuals in the club scenes, the film never shows Steve having sex. Whatever his relations are, they are conveyed through ellipses.

The subtlety the film shows with Steve is not afforded to the killer. While he is barely shown, when he is, there is nothing to him. He is not turned into an icon or an unseen menace. His character is not important in that way.

What we see of him de-mythologizes him, while the film’s increasingly fractured view of Steve makes him seem more remote and unknowable. Stylistically, the film is shifting their roles, transforming our protagonist until he has essentially taken the killer’s place - or at least is occupying the same space.

The movie climaxes with mirroring - during the final confrontation, Steve is dressed like the killer (even to the extent of stealing his hat).

When he stabs the killer, it is framed and blocked almost as if he has transformed into the same position, by his confusion and desire to exorcise himself of desire.

The film ends with a second, more literal example of mirroring: while Steve stares at himself in the mirror, outside his girlfriend (Karen Allen) puts on his leathers.

Despite the end of the case, Steve cannot leave it behind.

Related

If you enjoy something I wrote, and want to support my writing, here’s a link for tips!

No comments:

Post a Comment