Flatliners

Trying to figure out if there is something after death, a group of medical students intentionally stop their hearts to experience death and see if there is something on the other side. After they return, they realise that they have brought something back with them...

In advance of the remake, I took a look at the original Flatliners, directed by Joel Schumacher and starring Kiefer Sutherland, Kevin Bacon and Julia Roberts. I had never seen it before. Watching the original, it felt like a great premise looking for a great movie. It had a good cast, and some great photography from Jan De Bont, but my god is the movie corny. And while the concept sounds terrifying (what if your sins came back to haunt you?) the 1990 movie never goes anywhere that dark.

Watching the remake (directed by Niels Arden Oplev), a couple of aspects stood out.

In terms of characterisation, the remake is a big step up from the 1990 iteration. With the original, the characters felt like sketches - with this one, the filmmakers have come up with a group of clearly defined characters with a believable motivation for joining together on this crazy experiment. In the original, the characters were united by a sense of hubris - a belief that, since they were the most talented students in the school, they could handle the experiment they were undertaking.

With Flatliners '17, the characters are driven by their own personal motives which are then fed into the particular 'sin' that haunts them. Courtney (Ellen Page), the instigator of the experiment, is driven by a desire to see a loved one who she wronged. Unlike Kiefer Sutherland's lead from the original, she uses guile to get the other characters to help her. More believably, two of the characters, Ray (Diego Luna) and Marlo (Nina Dobrev) are not even a part of the experiment and are pulled in when Jamie (James Norton) and Sophia (Kiersey Clemons) are unable to revive Courtney.

The characters and their sins feel far more interesting, and the movie focuses on how each character is struggling to deal with the pressures of medical school. Related to this is a subtext about class and privilege which is missing from the '90 version. Marlo and Jamie are from wealthy backgrounds - while Marlo has worked hard, she is also carrying a dangerous level of self-belief in her worth as a doctor, and has used that as an excuse to cover up a crime that could jeopardise her future. Jamie is a rich playboy with no real interest in medicine - he's coasting through school, living on a boat and a steady diet of one night stands. His only goal is to become the next celebrity doctor.

|

| Jamie, the movie's resident d*bag |

|

| Sophia. She doesn't like Jamie that much |

This leads me to my next point: the execution of the 'flatlining' concept. In the original, the characters experience slight augmentation of their mental facilities, but the filmmakers do not dwell on it. Here, the filmmakers show how the experience does benefit them (Jamie gets smarter; Sophia gets the confidence to leave home). It gives the other characters a reason to try it. And once the cast have 'flatlined', the movie exploits the premise in ways which relate back to their characterisation. It gives the movie a bit of a kick when events start to go out of control.

Watching the original, my biggest issue was that the characters' sins, the punishments they had to endure, and the manner n which they were resolved, all felt underwhelming. No spoilers, but no one died in the 1990 movie, a factor which really undermined the experience - there were no real sense of stakes. In the new version, this aspect is amped up so that the movie actually manages to be scary. Going back to characterisation, each character's sin feels like an extension of their character, and so their eventual redemption (or lack there of) feels more earned. And unlike the original, there are real consequences for the cast - and not everyone makes out alive.

Even with these qualities, the movie is no masterpiece.

The direction was a little puzzling - maybe it was just the aspect ratio, but there were a couple of sequences where I felt like I was watching a TV pilot - it had a televisual aesthetic, but with a bit more money and style behind it. There were also some incredibly cheesy scare moments which relied too heavily on jump cuts and sound design. There were a few cool mis-drirects, but they were in the minority.

And while I enjoyed the concept of flatlining here more, I felt the movie was a little fuzzy around the rules of the sins and how they interact with reality. I did enjoy the fact that the movie does not stop for a massive exposition dump - the filmmakers focus on showing not telling, and it makes the movie less cheesy than it could have been. However there were a few set pieces where I felt the internal logic was a little inconsistent.

When I was walking out of the movie, two questions were running through my mind: Did I actually like the movie, or did I like it more in relation to the original? If I saw this movie with no knowledge of the original, would I like it?

Even with these qualities, the movie is no masterpiece.

The direction was a little puzzling - maybe it was just the aspect ratio, but there were a couple of sequences where I felt like I was watching a TV pilot - it had a televisual aesthetic, but with a bit more money and style behind it. There were also some incredibly cheesy scare moments which relied too heavily on jump cuts and sound design. There were a few cool mis-drirects, but they were in the minority.

And while I enjoyed the concept of flatlining here more, I felt the movie was a little fuzzy around the rules of the sins and how they interact with reality. I did enjoy the fact that the movie does not stop for a massive exposition dump - the filmmakers focus on showing not telling, and it makes the movie less cheesy than it could have been. However there were a few set pieces where I felt the internal logic was a little inconsistent.

|

| Vaguely relevant picture |

In comparison to the original, Flatliners '17 is a massive improvement. The performances are solid, the premise feels more fleshed out and there are a few decent scares. Unlike the dour original, the movie also has a sense of humour.

However, ultimately I don't know if this movie is good enough to stand on its own.

However, ultimately I don't know if this movie is good enough to stand on its own.

It's a decent remake, but unless you know the original I think you could get more mileage out of re-watching one of the Final Destination movies.

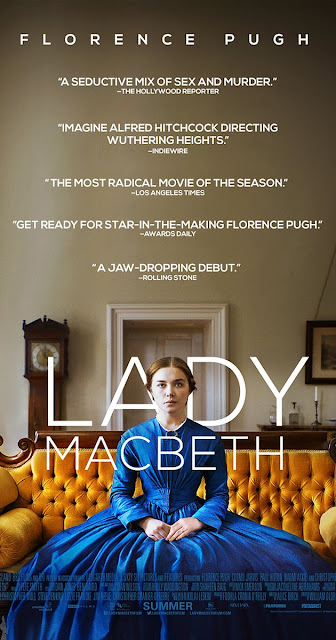

Lady Macbeth

A young woman, Catherine (Florence Pugh), is married to a wealthy man who imprisons her in his large house and spends no time with her. Eventually, Catherine acts out and falls for a rough groomsman (Cosmo Jarvis). Desiring more control over her destiny, she takes drastic measures to ensure her happiness.

It is a rare treat to go into a movie with no context. I cannot remember the last time I went into a movie with no idea what it was about. Before going further, if you are interested in watching this movie, don't bother with this review - just go watch it.

Lady Macbeth

A young woman, Catherine (Florence Pugh), is married to a wealthy man who imprisons her in his large house and spends no time with her. Eventually, Catherine acts out and falls for a rough groomsman (Cosmo Jarvis). Desiring more control over her destiny, she takes drastic measures to ensure her happiness.

The title is something of a misnomer. Based on an 1865 Russian novel, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, it is a shorthand for the main character's murderous intentions. Adapted by playwright Alice Birch (Revolt. She said. Revolt again), the location has been moved to 19th century Victorian England, a suitably terrifying context for the novel's focus on nightmarish gender restrictions.

Directed by William Oldroyd (it is his debut), Lady Macbeth is a chilly affair. Costing about half a million pounds, the movie benefits from its limitations. The action is largely restricted to the house and immediate surrounds, which works for the sense of confinement that Catherine experiences. There are only a few characters in every scene - we get enough extras to get a sense of the scale of the estate, but it also works for the characters' sense of isolation.

The photography reinforces this isolation, framing characters in single shots, or cutting from long shots to tight close-ups. Scenes in the house are framed in repetitive patterns and formal composition, with few variations in shot choice or editing pattern. It often feels like the characters are caught in an endless loop of routine and ritual. Scenes are bracketed by exterior shots of fields and forests obscured by fog - in this place, even the elements are restrictive.

As far as the acting goes, Pugh is the standout. Her understated, venomous performance provides the pitch black heart to proceedings, as she moves from being a sympathetic victim, to sardonic rebel to cold-blooded murderer. As her lover, Cosmo Jarvis is also good - especially once he becomes a partner in one of her murders, and begins to unravel. As Catherine's traumatised maid Sarah, Naomi Ackie is given an extremely limited palette to work with, but wrings a lot of sympathy out of the role.

While it is to draw comparisons with gothic literature (ala Wuthering Heights), the genre this movie is most aligned with is film noir. While noir is associated with the forties, detectives and mysteries, like all genres, the definition of a noir is more elastic. While there are many different definitions, for me the genre boils down to a protagonist (or 'fall guy') who is trapped in a series of events that he (or she) cannot control. The defining aspect of the genre is that the noir protagonist rarely escapes their predicament (think back to Double Indemnity, In A Lonely Place or the more contemporary Chinatown).

In Lady Macbeth, Catherine is not just a femme fatale, but is a victim of circumstance. Her control over the situation is never absolute, and she never attains the freedom she desires - at the end she is trapped in an empty house with a baby on the way. Despite her schemes Catherine is ultimately a fall guy stuck in a situation she cannot control. She is a poor woman whose marriage is framed as a financial transaction. Trapped inside her husband's house, under the thumb of her puritanical father-in-law, and abandoned by her husband, she eventually cracks under the pressure. Once she kills, she does not discover freedom but more pressures that push her further away from her goals. At that level, Lady Macbeth is interesting. But what makes the movie genuinely incisive and troubling, is the way the movie frames gender inequalities through the lens of white privilege - in this case, Catherine's relationship with Sarah.

Framed in the background, or lower within scenes, Sarah is the genuine victim of the system. She is the reason why Catherine never faces any real retribution for her sins. It is not cleverness which saves Catherine but her status which shields her from punishment. When her schemes backfire on her, she uses the people below her on the social food chain as scapegoats - and none is worse off than Sarah, someone who is incapable of fighting back.

Enough rambling. Lady Macbeth is a bleak but incredibly engrossing picture, and one of the best films I have seen this year. Go check it out.

Directed by William Oldroyd (it is his debut), Lady Macbeth is a chilly affair. Costing about half a million pounds, the movie benefits from its limitations. The action is largely restricted to the house and immediate surrounds, which works for the sense of confinement that Catherine experiences. There are only a few characters in every scene - we get enough extras to get a sense of the scale of the estate, but it also works for the characters' sense of isolation.

The photography reinforces this isolation, framing characters in single shots, or cutting from long shots to tight close-ups. Scenes in the house are framed in repetitive patterns and formal composition, with few variations in shot choice or editing pattern. It often feels like the characters are caught in an endless loop of routine and ritual. Scenes are bracketed by exterior shots of fields and forests obscured by fog - in this place, even the elements are restrictive.

As far as the acting goes, Pugh is the standout. Her understated, venomous performance provides the pitch black heart to proceedings, as she moves from being a sympathetic victim, to sardonic rebel to cold-blooded murderer. As her lover, Cosmo Jarvis is also good - especially once he becomes a partner in one of her murders, and begins to unravel. As Catherine's traumatised maid Sarah, Naomi Ackie is given an extremely limited palette to work with, but wrings a lot of sympathy out of the role.

While it is to draw comparisons with gothic literature (ala Wuthering Heights), the genre this movie is most aligned with is film noir. While noir is associated with the forties, detectives and mysteries, like all genres, the definition of a noir is more elastic. While there are many different definitions, for me the genre boils down to a protagonist (or 'fall guy') who is trapped in a series of events that he (or she) cannot control. The defining aspect of the genre is that the noir protagonist rarely escapes their predicament (think back to Double Indemnity, In A Lonely Place or the more contemporary Chinatown).

In Lady Macbeth, Catherine is not just a femme fatale, but is a victim of circumstance. Her control over the situation is never absolute, and she never attains the freedom she desires - at the end she is trapped in an empty house with a baby on the way. Despite her schemes Catherine is ultimately a fall guy stuck in a situation she cannot control. She is a poor woman whose marriage is framed as a financial transaction. Trapped inside her husband's house, under the thumb of her puritanical father-in-law, and abandoned by her husband, she eventually cracks under the pressure. Once she kills, she does not discover freedom but more pressures that push her further away from her goals. At that level, Lady Macbeth is interesting. But what makes the movie genuinely incisive and troubling, is the way the movie frames gender inequalities through the lens of white privilege - in this case, Catherine's relationship with Sarah.

Framed in the background, or lower within scenes, Sarah is the genuine victim of the system. She is the reason why Catherine never faces any real retribution for her sins. It is not cleverness which saves Catherine but her status which shields her from punishment. When her schemes backfire on her, she uses the people below her on the social food chain as scapegoats - and none is worse off than Sarah, someone who is incapable of fighting back.

Enough rambling. Lady Macbeth is a bleak but incredibly engrossing picture, and one of the best films I have seen this year. Go check it out.

No comments:

Post a Comment